The Cascade Institute’s executive director, Dr. Thomas Homer-Dixon, on “Global Warming in the Pipeline” by James Hansen et al.

“I’ve been talking a lot about this article, which was released as a preprint last December, issued in revised form in May, and was published earlier this week in Oxford Open Climate Change. I keep returning to its implications in my mind over and over again. I’d rank it as the most important scientific article I’ve read in the last decade.

Hansen remains the world’s most renowned climate scientist; and in the decades since his famous testimony before the US Senate in July 1988, he has consistently been ahead of the curve in his assessment of global warming trends and their implications. This article, which pulls together an enormous range of modeling and paleoclimate evidence, is the culmination of many years’ work by him and his team. They argue that the IPCC consensus greatly underestimates the degree and rate of future climate warming.

The paper is highly technical and requires close reading. The abstract doesn’t do it justice, so I’ve prepared below an accessible summary of its nine main points, with a few supporting quotations and figures.

If Hansen et al. are right, the received wisdom of today’s supposedly informed climate cognoscenti—people like David Wallace-Wells of The New York Times—is substantially wrong. Wallace-Wells, Roger Pielke Jr. and others tell us, with evident relief, that warming will likely peak somewhere around 2-2.5 degrees C. They say that “worst case” climate scenarios of 4°C+ are now off the table, because the rapid decline in renewables’ cost has rendered highly implausible the IPCC’s “business as usual” emissions trajectory—RCP 8.5, which assumes most of the world’s coal reserves will ultimately be burned. But this paper shows that we don’t need to burn all our coal to get something resembling an RCP 8.5 climate, or worse.

Now, to be clear, some prominent climate scientists vehemently disagree with Hansen and his team—Michael Mann being one. But Mann’s response to this paper on Twitter is little more than a cursory, hand-waving dismissal. Having studied climate research for decades, I think the balance of evidence weighs substantially in Hansen’s favor. Recent increases in tropospheric temperature suggest warming is indeed accelerating, and Hansen et al. convincingly show why that might be the case.

After I presented these findings at a recent meeting, my friend and colleague Tom Rand asked me “What do we do with this?” It’s a reasonable question. I think the paper has four immediate implications:

- What I’ve been calling the “enough vs. feasible dilemma” is likely even more extreme than I’ve previously argued. (The dilemma arises from that fact that policies that might be enough to effectively limit warming aren’t politically, socially, or economically feasible; while policies that are feasible won’t be enough.) So our responses to the climate crisis must be far more radical than we’re currently envisioning. Incrementalism is now a waste of time and resources.

- Heating this century is likely to overwhelm nature-based solutions to climate change. Fires and/or droughts will kill tree plantations, while heating will have major, and likely deleterious, effects on the biological processes that practices like regenerative agriculture must exploit to sequester carbon in soil.

- Multi-meter sea-level rise is likely to occur within the expected lifespan of coastal infrastructure being built now. (This rate of SLR is many times greater than the IPCC currently predicts.)

- The most dangerous aspect of the climate problem is the long lag between emissions and full climate response. “The large global warming in the pipeline today is not widely appreciated. Civilization and its infrastructure are not set up for a 2×CO2” This lag facilitates denial and delay; and by doing so, it increases the likelihood that some nations will ultimately attempt solar radiation management under emergency conditions and without enough advance research to minimize catastrophic side-effects.

“Global Warming in the Pipeline,” synopsis:

Hansen et al. make nine major arguments:

- Earth’s climate is significantly more sensitive to carbon dioxide emissions than conventionally estimated. Taking into account fast feedbacks—for instance, those involving clouds, water vapor, snow cover, and sea ice—equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS, or the eventual warming produced by a doubling of CO2 concentrations, holding ice sheets and vegetation constant) likely exceeds 4°C, rather than the conventional “best estimate” of 3°C (IPCC AR6).

p.12: “We conclude ECS is at least approximately 4°C and is almost surely in the range of 3.5-5.5°C.” - Conventional estimates of sensitivity assume too little warming following previous ice ages; but new paleoclimate evidence indicates that the coldest period of the last ice age was several degrees colder than generally assumed. There’s a fundamental disconnect between current climate models and the latest paleoclimate data on post ice-age warming. p. 12: “The IPCC AR6 conclusion that 3°C is the best estimate for ECS is inconsistent with paleoclimate data.”

- Higher sensitivity means that far more warming is “in the pipeline” (i.e., still to come, even if all carbon emissions stopped immediately) than conventional models predict.

p. 13: “If ECS is 4°C, more warming is in the pipeline than widely assumed. The greater warming could eventually make much of the planet inhospitable for humanity and cause the loss of coastal cities to sea level rise.” - When the effects of greenhouse gases additional to CO2 are counted, Earth is already experiencing greenhouse-gas climate forcing equivalent to a doubling of pre-industrial CO2 concentrations (p. 9). Forcing of twice this magnitude (i.e., equivalent to four times pre-industrial CO2) is “possible, perhaps likely, within a century.”

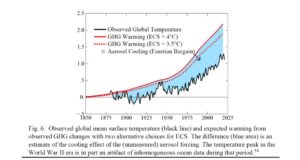

p. 4: “ [Four times] forcing is larger than estimates of the forcing that drove the largest known rapid global warming, the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) which occurred [56 million years ago]. The CO2 increase that drove PETM global warming was introduced over a few thousand years. The net human-made climate forcing has been growing rapidly only since about 1970, i.e., for about half a century, but within another century it could match or exceed the PETM forcing, while being introduced 20 times faster.” - To date, a significant portion of greenhouse-gas forcing has been offset by human aerosol emissions—”fine particles in the air that reflect sunlight and cool the planet”—but this offsetting effect is now declining, as key sources of pollution (especially from shipping and Chinese power plants) are cleaned up.

p. 17: “Aerosol cooling is . . . a Faustian bargain. Payment comes due as we reduce pollution from shipping, vehicles, industry, and power plants.”

- Because of increased growth rate of greenhouse gases and reduced human-made aerosols, Earth’s energy imbalance (EEI) has recently soared. (Hansen and colleagues define EEI as “the net gain (or loss) of energy by the planet, i.e., the difference between absorbed solar energy and emitted thermal (heat) radiation.”) Ten years ago EEI was about 0.6 watts per square meter, averaged over six years. Now “it appears, EEI has approximately doubled, to more than 1 W/m2” (accompanying explanatory post, Dec 22). Aggregated across the planet’s entire surface, this imbalance is injecting the energy of more than 600,000 Hiroshima bombs a day into Earth’s atmospheric-ocean system. Currently, most of this excess energy is melting ice and heating the ocean.

- This EEI change is accelerating the rate of atmospheric warming, from 0.18 degrees per decade (1970-2010) to an estimated 0.27 degrees per decade (2010-2040), an increase (in the rate of the rate, or second derivative) of about 50 percent.

p. 33: “Global warming should reach 1.5°C by the end of the 2020s and 2°C by 2050 (Fig. 19).”

p. 33: “Global warming should reach 1.5°C by the end of the 2020s and 2°C by 2050 (Fig. 19).” - Incorporating the full effect of slow feedbacks (e.g., ice sheet and vegetation changes) in Earth’s climate system, some of which operate over millennia, and eliminating the offsetting effect of human aerosols, raises ultimate equilibrium warming, given emissions to date, to 10°C. In their revised draft (recently released), Hansen et al. provide a detailed analysis of changes in CO2 and temperature over the entire Cenozoic era (the past 66 million years) to estimate equilibrium warming, given emissions to date. They establish that “the present greenhouse gas forcing is 70 percent of the forcing that made Earth’s temperature in the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum [50 million years ago] at least +13°C relative to preindustrial temperature.”

- The current change in greenhouse-gas forcing is so large and occurring so quickly that some slow feedbacks are kicking in faster than previously anticipated. “A large ice-sheet response and several meters of sea level rise are likely on the century time scale in response to continued extraordinary climate forcing” (p. 19).

p. 34: “Exponential increase of sea level rise to at least several meters is likely if high fossil fuel emissions continue. . . . [The] time scale for loss of the West Antarctic ice sheet and multimeter sea level rise would be of the order of a century, not a millennium. Eventual impacts would include loss of coastal cities and flooding of regions such as Bangladesh, the Netherlands, a substantial portion of China, and the state of Florida in the United States. For practical purposes, the losses would be permanent. Such outcome could be locked in soon, which creates an urgency to understand the physical system better and to take major steps to reduce the human-made drive of global warming.”

The implications of this scientific article on global warming, as outlined by Dr. Thomas Homer-Dixon, are staggering. The potential underestimation of climate sensitivity and the rapid changes in Earth’s energy imbalance demand a radical shift in our approach to the climate crisis. The urgency to understand and address these challenges is emphasized, particularly in the context of sea-level rise and the long lag between emissions and climate response. The article prompts a reevaluation of current climate narratives and calls for more immediate, impactful actions. What are your thoughts on the urgency conveyed in these findings

Selecting the most important scientific article of the last decade is subjective and varies across fields. Notable breakthroughs include the discovery of the Higgs boson, advancements in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, and significant progress in climate science and artificial intelligence. The choice depends on the specific area of study and its impact on scientific understanding.

Thank you for this crisp synopsis of Hansen’s paper. We are looking away at precisely the time that history demands us to pay close attention to what we are collectively doing to our planet – and how the planet is responding. James Hansen has yet another critical message for us but we continue to witness a stunning lack of urgency displayed by our governments, the willful denial of the facts by the oil & gas lobby, and a general population that is understandably more concerned with the ever-pressing challenge of making ends meet.

As many commentators agree, we are ill-prepared to meet the ravages that are currently at our doorstep, let alone future amplifications. When I am asked how bad the situation is (for those few interested enough to ask) I answer, truthfully, that it’s worse than we imagine – but I always add that we have solutions at hand if only we accept the rapid pace of investment required.

Lately I have become far less optimistic that we can deliver at scale, the social, technological, and ecological measure that are necessary to ensure resilience to climate extremes, largely because the political will is simply not there. At what point do we employ the fear of impending catastrophe to convey our message, and how does the lobby for urgent climate action become a more potent force than the lobby for the increasingly dangerous status quo?